In 2023, Get Closer To Your Coffee

Coffee is crowded and complex stream: here's how to get closer to your morning cup.

I like to start each year at Boss Barista by sharing a goal or intention for the months ahead. At the beginning of 2021, I wrote an article about how to start a podcast. In 2022, I encouraged readers to start a union—I wrote this piece just a few weeks after a Starbucks in Buffalo became the first location of the megachain to unionize, and I couldn’t have foreseen how massive and wide-sweeping this movement would be.

Now, in 2023, I’d like to encourage you to get closer to your coffee. But what does that mean?

A few months ago, I chatted with a coffee friend who said something I haven’t forgotten, but hadn’t been able to contextualize until now. He said he was uninterested in coffee businesses or ideas that lengthen the distance between farmer and consumer.

Just days before Christmas, the flash-frozen coffee startup Cometeer made headlines by announcing a series of layoffs. Cometeer, based in Massachusetts, uses proprietary technology to extract and concentrate the flavor from coffee beans, which it then flash-freezes into small capsules with nitrogen to preserve freshness. No machinery required: All you have to do is melt the frozen capsule to get a cup of coffee that promises to be as good as a freshly made brew.

I’ve tried Cometeer before. It works with many roasters I respect, and I remember telling someone how mad I was at how much I liked the coffee (I even made a video about trying their coffee). But brands like Cometeer are exactly what my friend had in mind when he mentioned being wary of companies that insert themselves into the supply stream.

According to the Specialty Coffee Association, there are approximately 27 different actors responsible for getting coffee from the farm to your cup—a number that former guest of the show Jim Ngokwey mentioned in an article he wrote for Daily Coffee News, and a topic which has come up before in this newsletter. Many of these actors are vital players: You wouldn’t expect the person who harvested your coffee beans to be responsible for the shipping and importing logistics required to transport that coffee around the globe, for example. This is different from what my friend had in mind when he referenced the people who use the guise of innovation to squeeze themselves into an already-crowded and complex stream, and it’s important to consider why they’re joining the long list of actors—and who stands to gain or lose from their inclusion.

Startups and other businesses like these often sell themselves as “disruptors,” seeing their purpose as upending how a particular industry operates. In some cases, these disruptions are welcome and necessary, particularly for underserved groups: courier-based technology brands can bring goods to rural or hard-to-access places; grocery delivery apps can deliver food to homebound or immunocompromised people.

But in other instances, technology brands that promise disruption aren’t just unnecessary but actively work to demolish the entire systems they were meant to “fix.” We’ve seen this play out with Uber: One of the appeals of the app-based taxi service was its prices. Uber (and then Lyft) rides were much cheaper than traditional taxis, which paved the way for ridesharing’s ascendancy. I remember living in New York in the early 2010s and a friend texting me a code for five free rides from Lyft, which is part of how these particular rideshare apps became embedded in consumers’ phones. When I moved to San Francisco in 2015, all Lyft rides within a particular section of the city were $5 flat. Furthermore, ridesharing apps addressed systemic inequities in public transportation and access to taxi services.

Rideshare apps made the taxi industry obsolete, and now that they’ve completely overtaken taxis, prices are skyrocketing. An article in Slate called “The Decade of Cheap Rides is Over” reports: “Average Uber prices rose 92 percent between 2018 and 2021, according to data from Rakuten; a separate analysis reports an increase of 45 percent between 2019 and 2022.” The article continues: “It’s the end of a decade in which we changed our systems, our habits, even our architecture, around the assumption that we could be driven around for cheap.”

We destroyed an existing industry for the promise of something better and more affordable, and once these new systems were locked into place, that promise was shattered. As the Slate article points out, “Once it killed off car service, taxi cartels, and its ride-hail rivals, the company would stop charging riders less than it was paying drivers and prices would have to go up. On Monday morning, an Uber from Manhattan to JFK Airport was $100—nearly double the fixed yellow cab rate. But good luck finding a yellow cab!” Beyond soaring prices and driver shortages, Uber has also devastatingly affected the wellbeing of taxi drivers (CW: this linked story discusses self-harm). We’ve paid a financial tax for this “disruption,” and an irreversible human one.

Of course, only some technology platforms and companies attempt to upend entire industries, and indeed only a few at the scale that ridesharing apps have. But the bulk of these actors work the same way: They put themselves in the middle of a transaction and, if successful, make it nearly impossible for those on either side of the interaction to opt out. Think about food delivery apps and how often restaurants are added to their platforms without consent, or the fees many of these services charge restaurants. One restaurant owner told CNN: “If you’re not on Seamless, ‘you no longer exist online. You’re not there.’ Because so many people order through the app, turning it off would mean losing about 80% of his business overnight, he said.”

Many technological startups are designed to cannibalize the very industries they’re meant to “disrupt.” Ridesharing apps have already done so—it’s impossible to get an affordable ride, which was the very promise the apps were built on. And while food delivery apps haven’t quite destroyed the restaurant industry, they’ve made an indelible mark the industry is unlikely to recover from. When a technological startup doesn’t wholly consume an industry, they’re painted as a failure. Initially, I wrote this section thinking that grocery shopping apps were an example of a start-up “disruptor” coexisting happily with in-person shopping—grocery apps haven’t shuttered supermarkets or limited our ability to shop in store—but apps like Instacart seem to be in big trouble because they have been unable to permanently change the way consumers shop for groceries.

This isn’t to say all tech companies are bad, and we cannot overstate the benefit to people for whom these apps and services are vital and lifesaving. And the problem is different when we think of physical products versus app interfaces. But the complexities and questions remain the same: When someone seeks to “disrupt” an existing system, who stands to gain? Why are they attempting to disrupt the system in the first place? And are they really disrupting for the good of the system, or are they trying to render themselves irrevocably vital to a system for their own gain?

Coffee is an industry that can stand to experience some shake-ups. Going back to the 27 different actors across the supply chain, one way to think about creating positive change in coffee would be ensuring its value is equally distributed. Right now, only 10% of the value of green coffee stays within coffee-producing countries, so it’s easy to suspect the motives of any new entrant to the supply stream, given how inequitably profits are already shared.

My colleague Kristen Hawley has a newsletter about restaurant technology called Expedite. In a recent post, she wrote: “But what also seems at stake here is technology companies’ ability to define the future simply by disrupting the status quo. What’s newer is not necessarily better; building a business worth billions of dollars doesn’t mean it’s the correct way for any industry to move forward, no matter how many so-called visionaries say so.”

This quote stood out to me because new things can promise so much—one of Cometeer’s videos said it was “a new day on Earth for coffee.” But one company or industry disruptor’s assessment of “doing things differently” doesn’t necessarily serve the industry at large. And for so many of these technology-focused startups, it seems like the answer is always, “Let’s shove our way in and shake shit up,” without any fundamental understanding of an industry’s existing context, or any desire to make things better for the stakeholders that matter.

So in 2023, I’ll ask readers to get closer to their coffee. Coffee travels through so many hands to get to you, so how can you get a little closer? Here are some suggestions, some free, some not—hopefully, there’s one that can meet you where you’re at:

Follow farmers, producers, and coffee people in coffee-producing countries on social media. People who work directly with coffee should be the people we listen to when it comes to necessary and important changes the industry needs to make.

Buy coffee from the same producers every year (I got this idea from my friend and former guest on the show Brian Gaffney). Consistency matters in coffee: it takes months for a coffee to go from a farm to your cup, and many farmers depend on knowing well in advance who is going to purchase their coffee. Be a regular to a farmer.

Purchase coffee from roasters in producing countries—you’ll put more money into a farmer’s hands by working directly with roasters in producing countries.

Buy coffee directly from small roasters or your local coffee shop.

Buy directly from a small grocery store versus a big-box store, or buy coffee directly on a roaster’s website versus Amazon.

This isn’t a dig at technology. In fact, technology has had a profound impact on how farmers get access to information and has helped make many systems within the supply stream more transparent. Jim Ngokwey talked about being able to verify payments with producers through WhatsApp, and Karla Boza (who we’ll hear from next week) has discussed how social media has connected her with roasting partners.

Instead, I hope this plea helps readers frame and question how things are sold to us. When we speak about changing structures, how can our actions spark change and positively impact the people that need it the most? When a business sells itself as the next big thing, when it expands in a grandiose fashion, when it claims to fix something that maybe didn’t need fixing, what is it actually trying to say with its claims?

To really disrupt coffee, one of the many things we have to do is redistribute value—and one small way to do that is to get closer to your coffee.

Some stuff I wrote recently:

I interviewed Sahra Nguyen for TASTE about how most people have had Vietnamese coffee without ever knowing it.

I did an absurdly nerdy deep dive into coffee blooms and what the bubbles in your brew are telling you.

I wrote my first two articles for Food & Wine: how to grind coffee and how to make coffee using a French press.

I’ve found a lot of meaning and excitement in my role as managing editor at Fresh Cup, and I compiled some of my favorite stories throughout the year.

A list I made:

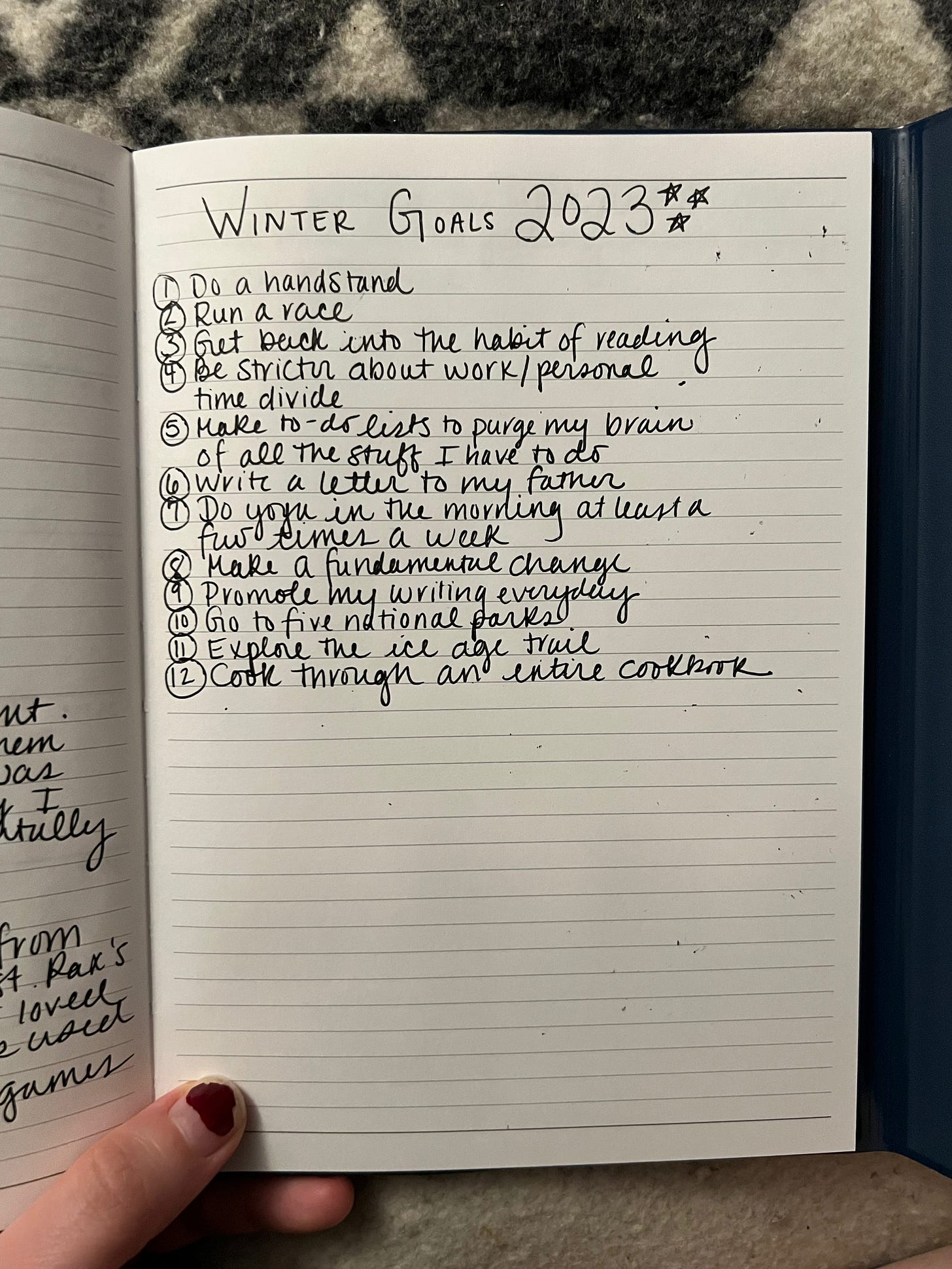

Every season, I try to make goals to give shape to the upcoming three months. I don’t always remember this, and if I do, many of my goals go undone. But it’s still a fun practice that provides me with structure and reflection. Here are my goals for this winter:

I also made a list of goals specifically for the newsletter, and if you’ve gotten to the end, I’d love to encourage you to do any of the following things:

Share this post with someone. Sharing pieces like this one on social media is the single-biggest driver of new email signups to Boss Barista.

Switch your subscription from free to paid. Boss Barista currently has 89 paid subscribers, and one of my main goals is to make this newsletter more sustainable in the future, and to have it constitute part of my income. Here’s a link to change your subscription.

Leave a comment! Words of affirmation are really gratifying for me, and connecting with readers feels really special.

Photo by Dang Tran

I don't drink coffee, but this is one of my favorite newsletters! Your discussions about industries at large definitely transcend just the coffee industry and your essays are always incredibly thoughtful <3

Thank you for this read, Ashley! I'm a coffee drinker, but I want to be more intentional with how I engage with. I never thought about how I could do this, so I appreciate all the tips!