The Hipster Barista Does Not Exist

How a decade-old meme came to define the way we view baristas.

Today, l’m sharing another one of my previously published stories from Standart, a magazine about coffee culture. This story is interesting: In 2011, the Hipster Barista meme spread like wildfire across the internet. Hundreds of publications picked up on the meme, writing articles not just about the image but about the person featured: a real barista named Dustin Mattson.

Ten years later, in 2021, I wanted to revisit the meme. I knew Dustin casually and asked if he’d be down to chat, and he was so generous with his time. He was also incredibly thoughtful and reflective about what the meme represents and how it affected his life. At the time, I saw the piece as a general interest story within the food world, but received no response from the dozen or so food publications I’d pitched. Thankfully, Standart always gives me the space to explore weird and interesting topics, and it immediately greenlit the story. This piece appeared in the magazine’s Summer 2022 edition.

Close your eyes and imagine what you think a barista looks like. A decade ago, one person became the literal face of “hip baristas,” and this image has fueled and shaped how we view baristas today. But does this person actually exist? Or is it through a series of unfair biases, machine learning, and bizarre internet culture that we’ve developed the image of the hipster barista?

In the summer of 2011, when Dustin Mattson was working for Octane Coffee in the city of Atlanta in the U.S., Octane scheduled a photo shoot for its employees. “Everyone was just being stupid and goofy the whole time,” he recalled when I spoke to him in a phone interview 10 years later. “We were just taking group photos and trading outfits. But eventually someone said, ‘We need at least one serious photo of you.’ So I posed, but I still had this scarf wrapped around my neck from when we were swapping clothes.”

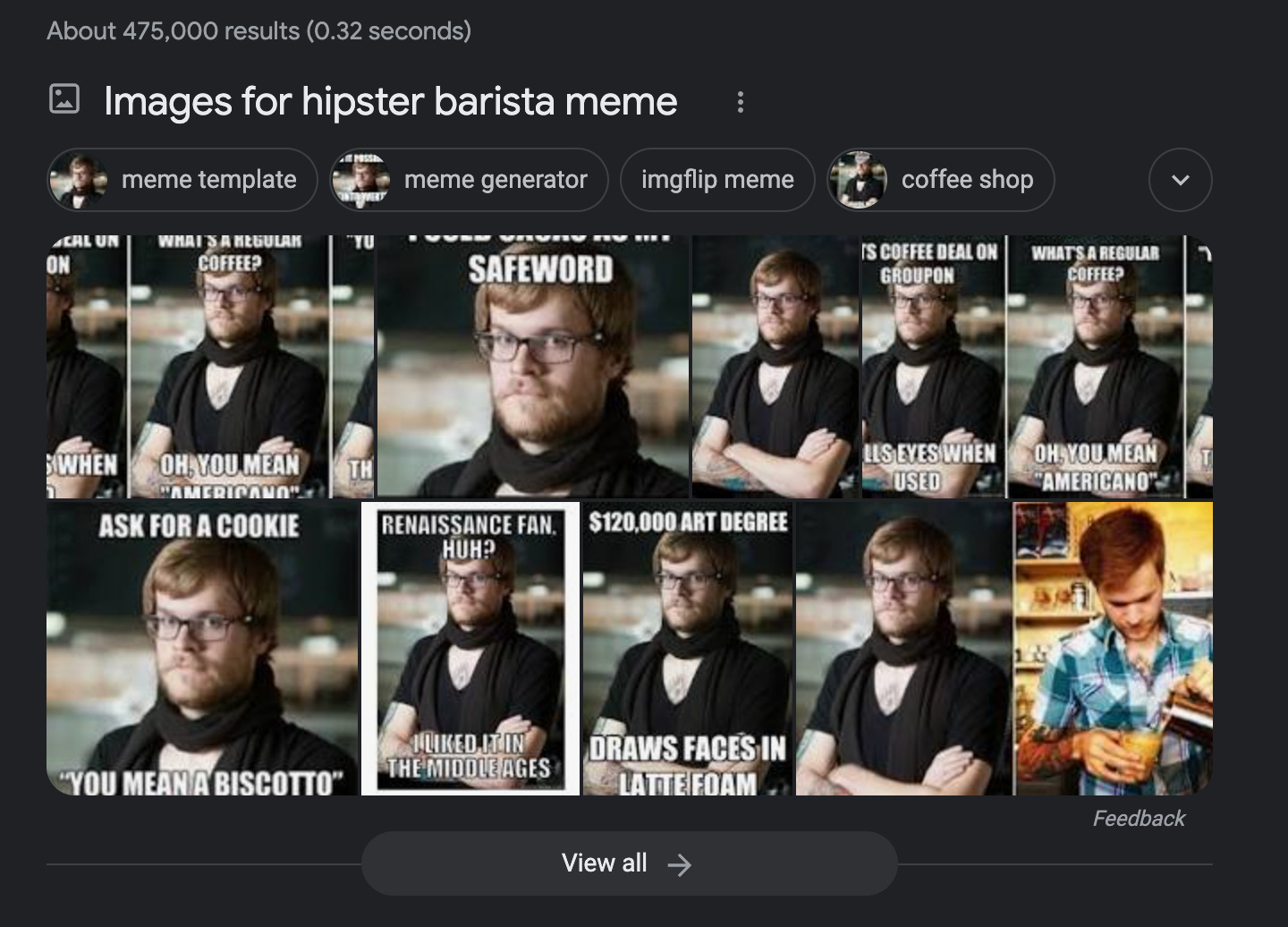

That photo ended up as Mattson’s profile on the Octane website, and became the basis for one of the Internet’s most iconic memes: the Hipster Barista. If you haven’t seen the meme, it became famous for one reason: It’s exactly what you think a hipster barista looks like. Mattson, a bearded white male, is wearing a black T-shirt with a deep V-cut neckline, a thin black scarf, and glasses, and posing with his arms crossed in front of him, revealing a number of tattoos. In its first iteration, the meme was accompanied by the caption: “I got this tattoo for my love of coffee / I got this one because it’s ironic.”

The guy I spoke to in July 2021, however, had none of that faux seriousness; he was affable and funny, and didn’t take himself too seriously. The guy in the meme doesn’t exist, and never did.

COFFEE’S VIBE SHIFT

Even though that ‘hipster barista’ is fiction, if asked to conjure up the stereotypical image of one, you’d likely describe Mattson’s meme photo without knowing it. Tattoos, facial hair, and bespoke glasses have become synonymous with a specific type of barista—you know what I mean: the ones who take their job incredibly seriously, cycle to work, and demand that patrons consume their coffee without milk or sugar.

But even if you imagine someone who looks like Mattson, because his appearance ties in with popular perceptions of Millennial hipsters, it can’t be denied that he was one of the first icons of a particular moment in coffee history. The Hipster Barista meme spread online during the first flourishing of meme culture in the smartphone era, which was also a period in which the coffee industry took itself perhaps too seriously—and customers noticed. Regardless of who Mattson actually is, his image came to represent, if not the entire specialty coffee industry, what it looked like to customers and outsiders.

In 2011, specialty coffee was smack dab in the middle of a vibe shift. Perhaps in order to differentiate ourselves from corporate coffee shops like Starbucks and legacy cafés with oversized couches and chalkboard menus offering cappuccinos in every size (think the communal hangout space encapsulated in the TV show “Friends”), we embraced the austere and serious: menus with only four drink options, reclaimed wood, no Wi-Fi, and condescending questions: ‘Do you know what a macchiato is?’

“I think these decisions represented insecurity,” says Sam Lewontin, a coffee professional based in New York City. “We’d all spent years and years developing this extraordinarily specialized skill set, and we all really wanted to be taken seriously. These attitudes were a way of projecting seriousness, or a reaction to the feeling that we weren’t being taken seriously.” In their desire to “elevate coffee,” baristas had genuinely become incredibly knowledgeable about coffee and skilled at making it, but often lacked the ability or patience to translate that passion to customers in an accessible way.

Lewontin moved to New York in 2010 and began working at Everyman Espresso in 2011. He was hired specifically to coordinate the opening of a second location of the store in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan, and one of the first discussions he remembers having addressed the reputation of specialty coffee as “too cool for school” and baristas as pretentious and aloof. “SoHo as a project was about figuring out how to codify how we felt about serving coffee,” Lewontin says. “Baristas have this reputation for being jerks, but you can't share [knowledge or passion with customers] that way.”

And Lewontin’s vision for the Everyman SoHo location tried to counter some of these preconceptions. There were no menus, for example, but this was in an effort to actually combat the idea of pretentiousness—baristas had to intentionally engage with every customer; but they were happy to step out from behind the bar to bring drinks to waiting patrons—admittedly a refreshing image, compared to the one we have of baristas hand-wringingly shouting customers’ names into the void as their drinks quietly die on the bar.

Were baristas actually pretentious jerks during that period? Maybe some were, but even so, those few culturally cemented the popular image of baristas. The television show “Girls,” which debuted in the same cultural era, featured a character who worked as a surly café manager at Café Grumpy, a very real café in the (ultra-hipster) Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn. The proliferation of the Hipster Barista meme is testament to the fact that as soon as the hipster coffee culture emerged, it was being lightheartedly mocked and parodied. In 2014, chef David Chang—the owner of Momofuku, one of the hippest restaurant chains in New York City—told GQ magazine that “coffee snobbery is just foreign to me; I don’t drink much coffee, because there is this great stuff called Diet Coke that has plenty of caffeine. It’s really refreshing, and I don’t need any tattoos to make it or fake Italian words to order it.”

After the Hipster Barista meme went viral, Mattson was interviewed by a number of media outlets including Eater, a food publication that reviews restaurants and cafés across the globe, who reported him as saying: “I do find it discouraging and disappointing that there was so much exposure brought to an attempt at making a joke of a culinary industry and the professional barista.” None of the mitigating factors such as the fact that the infamous photo was the product of a silly photo shoot, and that he had been directed to look comically serious, are even mentioned.

Mattson was ambivalent about his “infamous remark,” as he called it, in our 2021 interview. He made the comment “right when the Food Network was popping off. There were all these new shows celebrating cocktails bars, food culture, and sommeliers … and my opinion at the time was that it’s unfortunate that we patronize and revere these hot new restaurants and bars, but we don’t have the same respect for people making coffee in the morning.”

A SERIES OF TUBES

If you Google Image search the term “hipster barista,” along with the meme, you’ll probably be struck by the fact that almost every resultant image resembles Mattson—featuring a white man, many with facial hair and thick-framed glasses—while others are … more Mattson than Mattson, sporting handlebar mustaches, custom-waxed aprons, and man buns (when they’re not wearing a beanie).

Google made its Images search engine after millions of people tried to search for the green Versace dress Jennifer Lopez wore to the Grammys in 2000, and since then has continuously refined its algorithm to code and classify photos into categories of similar or relevant images. Basically, its algorithm is designed to get smarter over time. It’s why you can search for “Jennifer Lopez Versace dress” and “Jennifer Lopez Grammys,” and the top result is the same green dress. In 2022, images are more powerful and lucrative than ever. Mattson wryly admits that people have suggested that he issue an NFT to profit off the meme, but the idea strikes him as disingenuous because he doesn’t think that his image is representative of the larger barista community: “This dude is a caricature of an idea, but I’m a cisgender white dude who should be at the backburner,” Mattson says. “There are way more important conversations to be having.”

Lewontin freely acknowledges that many of his aesthetic choices in 2011 resembled those showcased in the Hipster Barista meme. “I wore skinny jeans and vests, and rode my bike everywhere,” he says. “Nobody really tried to imprint their ideas of what baristas were like on to me—or if they did, I didn’t notice—but I think that largely came down to my being in a position of privilege. A lot of folks I’ve worked with haven’t had it so easy.” In a way, Lewontin was able to become the barista he wanted to be because he aligned with the popular image of the barista among the general public in the U.S.

And despite the fact that it represented the popular perception of the barista, rather than the truth, even then the meme is very limited in scope. Although there’s no data on the gender breakdown of baristas, over 60% of all food servers in the United States are women, and many are people of color—and that’s just the United States, where Mattson lives. The results churned out by Google Images vary, depending on one’s location, so an image search for a “hipster barista” will elicit very different stereotypes if one is outside the United States. Such images pulled up in different countries might differ in terms of the barista’s appearance, but they will all suffer from the same problem: ideas about what we think a “hipster barista” looks like influence what we think a barista does and should look like, regardless of the reality of who’s actually behind the bar.

This is one of the common problems associated with tools that utilize machine learning: because they cull information made by humans, they also reflect societal biases. “Our online body of content is created by us—people—and to whatever degree the population that creates content is biased, that bias will show up in the content,” says Russ Maschmeyer, a project manager for Shopify. “This is a huge problem for machine learning systems that we’re building going forward in terms of equity and equality because so many of these systems will drive decision-making and determine access [to] opportunities.”

And this is no mere academic consideration; it has very serious real-world implications. If Mattson’s image is the symbol of what we think a barista looks like, there’s a good chance that coffee businesses are less likely to hire those who don’t look like him. The same logic can be applied to any industry. What do we think a doctor looks like, or a teacher, or an entrepreneur? When an idea becomes associated with a certain image, that association has the power to reinforce negative, even harmful ideas about the way we view the world.

THE EFFECT IT PRODUCES

In a letter to his friend Henri Cazalis, Stéphane Mallarmé described his artistic mission as the creation of “a language which must necessarily spring from a quite new conception of poetry, and I define it in these words: To paint not the thing, but the effect which it produces.” Mallarmé is one of the key figures of symbolism, an artistic movement that prefers to employ metaphor and representations to describe human truths. Fast forward to the present day, and memes can be thought of as a form of symbolic art. A meme isn’t usually about what’s being depicted, but about what the viewer feels when seeing it, or the connotations it arouses. Yes, a 19th-century style of art has a lot in common with esoteric Internet subcultures.

Nothing about the Hipster Barista meme is actually true, except in the mind and eye of the viewer. This meme, just as other depictions of coffee and baristas in popular culture, simply captures our perceptions of something; it encapsulates a moment in time, records a vibe shift in our culture, and constitutes a lesson in how others see us.

‘A meme isn’t usually about what’s being depicted, but about what the viewer feels when seeing it, or the connotations it arouses’

This whole essay was wonderful, but the paragraph toward the end - 19th C symbolism and 21st memes - was especially brilliant.