Boss Barista is a weekly newsletter and podcast series about workplace equity and employee empowerment in coffee and beyond. If you’re not already subscribed, welcome! I’m glad you found your way here. Before you go, sign up, will ya? Here’s a cute little button to make it easy:

If the following piece resonates with you, consider donating to my Patreon. Pledges of any size help me produce these stories, and your support is gratefully received.

In the last three years, there have been a number of unionizing efforts within the coffee industry. Baristas across the United States have come together to organize and demand accountability from their leaders. They’ve expressed the need to have a voice in decisions such as hiring and firing calls, wage increases, and workplace conditions.

We’ve covered a number of those efforts on previous episodes of Boss Barista. From the Gimme! Coffee Union in New York to the Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative (formerly known as the Augie’s Coffee Union), we’ve heard stories from coffee workers and organizers about the many ways in which those in power are threatened by collective action.

Not a single one of these unionizing efforts has been without strife or difficulty. The Gimme! Union folks were in negotiation with leadership for half a year before their union contract was ratified. All the baristas at Augie’s Coffee were fired. Mighty Good, which is a coffee shop in Ann Arbor, initially recognized the union started by its baristas, which formed after one of its employees, Nya Njee, shared that she was being paid less than her white colleagues, many of whom were hired after she was. Months later, the owners of Mighty Good shut down its retail locations and fired all baristas.

But there is hope in all this. More and more baristas are fighting for their rights, realizing the power of collective action and bargaining. Though unions may have a difficult reputation among workers for any number of reasons, at their core, they’re meant to help elevate the voices of those not in power, and to give space to workers who are often at the mercy of employers without any support networks.

Today, we’re chatting with two folks in the midst of a union battle—Zoe Muellner and Robert Penner of the Colectivo Collective. Consisting of baristas and other employees both in Chicago and Milwaukee, the union is still fighting for recognition by providing information to employees and garnering support from customers and local representatives.

In this episode, we talk about how unionizing efforts began, and what it feels like for your leaders to deny your concerns and complaints. The folks at Colectivo have highlighted the myriad ways their worries have been dismissed and their safety put on the line during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the union folks are attempting to bring accountability to their leaders and find a voice in the collective. Although they’re fighting for a better workplace for themselves, they’re also using social media to dispel common misconceptions about unions, and to keep folks informed and updated on ways to organize in their own workplaces.

If you want to hear more from the folks we mentioned above, as well as other coffee unions, check out our episodes with the Gimme! Coffee Union, Nya Njee, WACWA (the union formed by the Mighty Good baristas), Tartine Union, and the Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative.

Ashley: So before we begin, let's have you both introduce yourself? I'm going to start with Robert just because Robert was the first one on the call.

Robert: Hi. I'm Robert Penner. I am a now-former worker from Colectivo Coffee. I'm a resident of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I worked for Colectivo at a couple of different stints between spring of 2016 and then winter of 2017, and then again from 2019 into 2020. I was a warehouse and production facility worker there.

Ashley: Zoe, what about you?

Zoe: So my name is Zoe Muellner. I use she/they pronouns and I worked for Colectivo for just about two-and-a-half years—from August 2018 through October of this past year. I worked as a cafe co-worker. Then I was a lead barista, or lightning rod as Colectivo calls it. And then also worked my way up to being one of the barista trainers for the Chicago market.

Ashley: Where does the story of the union start for you folks?

Robert: I think there's kind of a parallel beginning to the union because, what I know, is that in the warehouse prior to COVID-19 there was a lot of frustration and this was coming in the fall and the winter of 2019. The workers in the warehouse were kind of being ignored.

We've got a lot of complaints about workplace processes, about changes that are being made without us being informed ahead of time, inconsistent ordering, and unsafe work practices. We also kept having our reviews, our yearly reviews, pushed back, which isn't good because that's how we get our raises. And so the more they push those back, the less time we have in that year to cash in on the raises that we're supposed to get.

And it was just kind of a thing where it's like, it says in the employee handbook that we'll have performance reviews in September—and September comes and goes, and we're like, “Okay, when's this going to happen?”

We're asking the COO Leo [Lettow] and we're saying, “Look, when are you going to do our reviews? We'd really like to have our reviews.”

And he's like, “Oh, we'll do them next week.”

And next week comes and goes, and we're like, “Leo, you said we would do our reviews next week. What are we going to do?”

And he's like, “Oh, we'll do them next week. We'll do them next week.”

And they get pushed all the way to December before we finally have to pressure them into doing these performance reviews.

They don't go by the handbook and it's totally a disorganized process. It was one of many complaints that we have in the warehouse, but it led us to try and seek out different kinds of action we could take.

And so me and a couple of the other warehouse people sought out the IWW, which is the Industrial Workers of the World, because they've run some pretty good direct action campaigns in Milwaukee. They helped us do a little bit of direct action in the warehouse where we as warehouse workers compiled a list of demands that we wanted to put forward when we went into our performance review meetings with Leo. We all went in with the same message and we were able to win a couple of small concessions there.

And that's really where the interest in unionizing, at least from the warehouse end, started. But then we realized later that there was also talk in the Humboldt cafe going on at the same time about unionizing. We didn't really know that back in the warehouse. I mean, we talk to people in the cafe a lot and work with them, but there's a little bit of a communication divide there. So we found out later that there was also union talk going on in the cafes in Milwaukee as well.

So that's kind of where the union efforts started—when both the warehouse people and the cafe people realized that they were both thinking about unionizing.

Ashley: Zoe, when did you first hear about union efforts starting?

Zoe: My first clue was around the beginning of the pandemic, a petition started that said, “Many cafes around the country are shutting down with two weeks’ pay. We would like to see that happen here. It's unsafe for us to work right now. We need to take a pause and figure out where the company's going and how we're going to safely handle the pandemic.”

And it got like, 4,000 signatures between the folks who work within the cafes and our surrounding community, which was amazing. And the company agreed to follow what the petition asked for. I think it was a couple months later, around the beginning of June, one of the other people on the VOC [volunteer organizing committee] approached me and said, “Hey, we're organizing. Is this something you'd be into?” And immediately I was so excited about it.

My only real familiarity with unionizing was through the television show Superstore. So just seeing what that was, I was like, “I don't know a whole lot about unions yet,” but I started attending meetings and really just jumped on board from there.

Ashley: It seems like information is a big component to union efforts, which is something that you folks tackle a lot on your Instagram account, which we'll talk about in a little bit, but I want to talk about the moment that you folks declared your interest in starting a union to the leadership at Colectivo. What was that moment like?

Zoe: It was nerve-wracking for sure. We sent a letter with a list of names of people who were on the volunteer organizing committee. We didn't hear a response back for probably about two weeks. There was no formal response, but you could tell that there was an energy shift, at least from the regional manager in Chicago. We had been very friendly before, we had talked about things going on in our lives—and then the day after the list went out, eye contact went down to a minimum. There was very little conversation. There's definitely a shift in how upper management dealt with us.

Robert: Yeah. And there's also a lot of buildup to it because we had been organizing for quite a while before we went public. And so going public was a big deal for us. That was the result of several months of work and organizing and communicating with union organizers in the IBEW—The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers—who we were unionizing with. It was a big moment and it was for sure nerve-wracking, because there were people's names that were on that list, including myself, that were not back to work yet. So that was just a very important moment and kind of a turning point in the union effort as a whole.

Ashley: What did your letter specify as some of the things that you wanted to see leadership address?

Zoe: We didn't have immediate demands right away because the company's so large—at the time, there were 19 cafes that were open, two were still closed down due to the pandemic, but we have the bakery, the roastery, warehouse workers, and drivers. So we didn't quite list demands right away because we figured that we were such a small contingent thus far that we didn't want to make decisions or have big statements that not everybody might agree with right away.

We essentially brought our names forward and said, “We want to unionize, and we want to work together. We would love it if you would recognize us. And that way, we can come up with a contract altogether that works for everybody rather than putting forth something that just focused on a few people that were involved right at the beginning.”

Ashley: So this was really a moment of goodwill on your part saying, “This is something that we're interested in and we want to work together to achieve something that works for everybody.”

Zoe: Absolutely.

Robert: Right. Yeah. And this has never been about destroying the company or hurting the company. This has always been something that we want to make a collaboration. But we need to be sure that workers are being treated fairly, that we're being treated with respect, that we’re being communicated with.

And so it was an act of goodwill and that goodwill really wasn't returned. Just to put it in that perspective, we're not trying to destroy Colectivo by forming a union, even though that's what the owners and upper management seem to think that we're doing. This could be a really major boon for the company to say, “We have a unionized workforce; it's producing some of the best coffee in the Midwest,” but that's not on their agenda.

Ashley: I like that you mentioned that because I have talked to other union organizers in the past about the optics of a union, even if management disagrees with the union, the optics of having a unionized workforce is probably some of the best marketing you can ever buy.

It's an interesting—not to say that's a good reason for recognizing a union—but it's one of those moments where you're like, “Are you doing anything good for your company? Why are you being so negative on so many fronts?”

Which comes back to that moment when Colectivo then responded, which has been covered on Eater and a couple of other local outlets. And some of the rhetoric that they used in that letter is wild. So I was wondering what that was like, receiving the response back from the Colectivo management team.

Zoe: I think “wild” is a good word.

With them being silent for about two weeks, there was a point where you're like, “Maybe they're not going to respond. That would almost be kind of nice!”

And then this letter went to everybody. It was one of those things where your entire face goes hot while you're reading it. You can tell that your face is red and you have so many feelings about it because there are things that are frustrating and things that are kind of demeaning and all of this rhetoric that is basically saying, “All of these things that you have worked towards, we either do the bare minimum, which should be just enough, or we don't do it at all, but it's not important. So you guys should just stop. We don't recognize it. This is not for you. And it shouldn't be.” And it it was pretty demoralizing.

Ashley: One of the things that the letter said was that, “A union would fundamentally change our culture.” I was wondering what that meant, because that was the point, right? The point was to change the culture, to make it more communicative! What did it feel like working at Colectivo before that? I don't know, this phrase “fundamentally change our culture” is really bothering me.

Robert: That was the main thing that bothered me too, was harping on this idea of our workplace culture, this sacred workplace culture, and my immediate response was, “Look, you wouldn't have a large portion of your workforce trying to unionize if your sacred workplace culture was so great.” You just wouldn't—you wouldn't see that.

And so I think that either they're trying to manipulate us with this or they're just totally out of touch. It could just be a combination of both, quite honestly. Because there need to be changes in the workplace culture. You have a workplace culture where management’s disrespect of workers is rampant, where there are expectations that are not communicated—and then you're disciplined for not meeting those expectations later that you had no idea even existed.

The culture is of not truly fixing things that are broken, not actually fixing equipment, or making sure that people are certified or using equipment safely. That's the culture: It's a culture of covering problems and putting this hip shiny facade over the inequities and inefficiencies in the workplace. That's their culture. That's the culture they're talking about. And really what they mean by that is, “We don't want to have to change things that we think are too expensive to change.”

Zoe: They have a saying in part of their mission statement where everybody is a customer and that includes, or it's supposed to include, coworkers. But I think a lot of us have not felt that for a very long time.

There might be an issue within a cafe where somebody who works there, or say within the warehouse, will voice what is going wrong or what issue there may be—and there might be no response from management, or there might be a “We'll look into it,” or some sort of placating response and nothing happens. But then if an actual customer who is spending money within the cafe says something, then a change happens, then you see immediate response, then you see something that will actually produce a positive change.

So that feeling like we're actually customers and that we're all in this together hasn't really been a through-line for quite a while, I would say.

Ashley: I think that reduces down to power, which I think nobody in upper management wants to talk about, right? No one wants to admit that this is a power struggle because when Zoe, as you laid out, when there's a transaction of money, a customer is giving money, therefore we're going to listen to them. But as a co-worker, that relationship is inverted. Your employer is paying you. Suddenly those power dynamics get totally shifted. So you're treated totally differently.

Zoe: I mean, I’ve seen one of my cafe managers not go on a break because the ownership was there. And they said, “Oh, at this point, I'm just a number. I can't go sit down and eat. I can't go on a break. They have to see me completely working 100% of the time.” That kind of culture is super unhealthy and toxic. And it feels like that's the kind of culture that is permeating the company at this point, rather than this supportive, boisterous [culture]—everybody lifting each other up and trying to work in tandem towards positive goals.

Ashley: There's another part of the letter that also is incredibly angering. “Camaraderie and respect would be replaced by workplace rules,” Which number one, as you laid out, there is no camaraderie and respect, and number two, wouldn't it be nice if some rules were enforced?

Zoe: Yeah!

Ashley: Like, yeah, take your 10-minute break! What did that feel like, reading that?

Robert: Oh, seriously, that sounds great to me! Workplace rules? That sounds great to me, because we work in this environment where there aren't these hard-and-fast rules, and that's so frustrating and it's demoralizing and it's inefficient and it's just not an effective way because it's all off-the-cuff.

So we have this employee handbook and you don't even know if it's up-to-date most of the time, and it's not followed.

Zoe: It can be changed at any time.

Robert: It's not a contract. It can be changed at any time. And upper management doesn't even follow it. Like I was saying with our performance reviews earlier, they just didn't follow it. I think that hard-and-fast workplace rules sound excellent to me, that would make things so much better for workers at the company.

I don't think they realize that—I think they want to come off as these lenient, cool … “Oh yeah, my boss, the owners of this company are awesome. We don't have workplace rules, we just kind of show up or we do our thing and everybody just kind of comes in and does it…” No! That's not actually the reality that exists in these workspaces. I don't think that the owners actually realize that. I think probably some of the management does. But there's so caught up in their inefficient and really kind of, as Zoe said, those toxic ways. They aren't really trying to make any changes.

Zoe: And it's so much easier to have camaraderie and fun at work when you feel listened to, taken care of, and safe.

Ashley: Yeah, absolutely. And from all angles, it also seems like rules would be easier to follow, too. For example, if I know that all of my employees get raises in September, I can plan a fiscal year around that, I can hire people based on projected wages and things like that.

So to me, it doesn't seem like it's a business decision. It's not about, like we were saying, money, which they talk about a lot in that letter—they talk about how the pandemic has affected their profits. It is 100% about power.

Like you were saying, Robert, they want to be the people who say, “We're cool, we're lenient. We don't need to enforce rules,” but that's a thinly veiled way of saying, “We don't want to let go of our power. We don't want to have to be forced to listen to other people when we want to be the ones ultimately making decisions.” It's almost like your parent telling you to do this thing because I said so.

Zoe: And if it was such an issue with money, then I think hiring the Labor Relations Institute—they had two people going around to the different cafes having captive audience meetings—and those folks charged $3,000 per day per person. So if money were really the issue, I don't think that they would have turned to the Labor Relations Institute to solve it because that cost them a pretty penny.

Ashley: Did you have to sit in on any of those meetings?

Zoe: Yep. It was very uncomfortable.

I definitely had to listen to some pump-up music in my car to feel any amount of confidence going into these. I was part of one that was at one of the cafes within Chicago, and there were a lot of worst-case scenarios. There was a lot of doomsday talk.

And at one point I talked about the Labor Relations Institute, because I had done my homework before going into the meeting and had looked up who was the person conducting the meeting, and found out that when he worked with FedEx to squash their union, that he got paid over $226,000 for about seven months’ worth of work with them. And he was one of, I think, six people who worked on that union-busting campaign. And when I said the term “union buster,” he lightly reprimanded me because apparently that's a derogatory term. So he got mad at me for using the term “union buster,” even though that company is legitimately on a Wikipedia article front page under “union busting.” It was wild.

Ashley: Yup. Yeah. I needed a minute with that. Whew.

Zoe: That was a lot.

Ashley: It’s kind of amazing that you had the foresight to do a bunch of research and come to this meeting incredibly prepared. And I think that shifts to how you folks have handled your social media messaging. If you go to the Colectivo Collective page, it's pretty much a rulebook explaining, “This is what union busters do to try to convince people that unions are bad.” So I was wondering how you folks thought about what sort of message you wanted to portray, because you're still in the middle of this fight.

Zoe: Absolutely. It's been evolving for sure. It's me and one other person—we've been the main folks who are running the Instagram page with varying degrees of help, as far as what people's bandwidth has been throughout the past nine months or so, because that's definitely been a variable.

I think a lot of it has just been somewhat responsive to how Colectivo has been handling themselves and what messaging that they have been using. We really want to talk about everything in a positive light as much as possible, because folks who work for Colectivo are probably getting their fair share of negative union coverage from the company itself. So we want to show the positive side and what things can be done and what things we can do despite what union busters or what the company might be saying.

Ashley: So let's talk about some of these things. What are some of the common union-busting tactics or rhetoric that are maybe not specific to Colectivo? I'm not sure if you can get too into that, but what are some of the things that you've seen or you've read that you've talked about on your Instagram account?

Zoe: Definitely the captive audience meetings. That was a big one, because if they are paying you to be at this meeting and they make it compulsory, then you have to be there. Pretty much everybody within the company had to attend one of those meetings over a period of two weeks or so. That's definitely a big one because we can only suggest and hope that you interact with our information and with our page, but they can force you to interact with union-busting scare tactics. I think that was probably the biggest one.

There’s also the rhetoric that went into the couple of letters that have come out, using doomsday phrasing like, “This union might be the wrong one for you,” and, “It's really hard to remove a union once you're already unionized. So you should just not do it in the first place.” It feels like there's almost too many things to mention.

Robert: They harp on money a lot, and one of the big things that’s just a total lie that came out in both of their main letters was they're saying, “Oh, the union is going to cost you money. Your wages are actually going to go down.”

First of all, IBEW would never sign a contract where our wages actually went down on account of dues. When you join a union, you do have to pay dues, but those dues would be very small and we would get to choose what we pay based on what benefits we want as union members from the union. And they said, “Oh, you're going to have to pay into a retirement fund.” Well, that's not true—if we don't want to pay into a retirement fund then we don't have to.

They're like, “Oh, you're going to have to pay a thousand dollars as a trainee fee.” It's like, “No, that's for journeymen electricians that join the union. This is a coffee workers union.”

So all of this stuff they’re trying to come up with to make it seem like we're going to have to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars to become union members—it's all scare tactics, it's all lies.

Even coming out with propaganda, the company saying, “We can't lie to you, but the union can.”

It's like, “No! You've been lying to us this whole way. And you're reversing the places that you're in because the union cannot make promises. The union cannot tell you untruths because they’ll be censored by the NLRB (the National Labor Relations Board) for that.”

The company is trying to reverse fields here and portray itself as the thing that's being aggressed against rather than them being the aggressors against their workers and against this union effort. It's very frustrating and they're trying a lot of different tactics. They've thrown the book at us to bust this and make people scared and make people fearful and feel animosity towards the union.

Ashley: It's interesting to hear you both talk about the way that Colectivo has used scare tactics, because it feels very applicable to the current moment in time that we're living in—where you’re almost being gaslit about what is true and what is not. And you have to keep your head above water to figure out that you know what's true and you know what’s right. And you have these people around you saying untruths and attacking even the way that you present information. And I wonder how has that felt emotionally?

Zoe: It's incredibly draining. We had meetings also with the CEO, Dan [Hurdle], and Leo, who's in charge of operations, and they wanted to come sit down with the Andersonville cafe. I have had somewhat of an issue for a long time with some of the imagery used in our messaging—stuff that uses the sugar skull, which is associated with Día de los Muertos. None of ownership is Latinx—it's three white men—and so a lot of people don't realize that it's not a Latinx-owned and -run company, and it feels like … it just feels a little crummy.

It’s on shirts and all of these things. So I suggested a T-shirt buyback program because it felt like it was taking advantage of cultures that don't belong to you. And the CEO was like, “Hmm, I hear what you're saying, but I don't agree.” And so it feels like there's a lot of like active listening “signaling” that happens within the company, but not any, “Oh, I understand what you're saying. I hear where you're coming from. Let's get together and let's make a positive change.”

Ashley: So I think if you folks are willing to talk about this—we don't have to talk about it—but both of you were let go at different times, and it seems like it was because of your union efforts. So I was wondering if you could talk about that.

Robert: Yeah. I can go first. I was laid off back in March when coronavirus really started to pick up. Initially, I had decided to opt out and I thought I was only going to be away from work for a couple of weeks. I don't think anybody knew the scope of what coronavirus was going to be yet.

So I had opted out for, I think two weeks is what they gave us as the opt-out period. And then shortly after that I was laid off. Since that time I had been looking for opportunities to try and get back to work, get back to the warehouse. I knew they needed help there because I communicate pretty regularly with some of my coworkers—they're my friends, I've known them for a long time. And they needed help.

They had lost people to the layoffs, to people quitting. I was looking for a way to get back. And so in the late summer I had told my manager, “I'm ready to come back. Whenever you need me, give me a call.” And he was like, “Oh yeah, for sure, for sure. We're going to do it.”

And a little bit later, at the end of September, I finally got the call and he said, “Hey, we need you back. And we're ready for you. Can you start on Monday?” And I was like, “Yes, that's awesome. I will be there.”

And I was pretty excited. I was excited to get back to it—not having any income for months and months is really, really tough. A lot of unemployment checks coming in at that time. And so yeah, I was excited.

But on the Friday before I was supposed to come back, I get a call from Leo, the COO, and he said, “Actually, we're not calling you back to work.” He was like, “Your floor manager overstepped his authority in calling you back. We're going to shift other resources around instead.”

And I said, “Well, what does that mean? I know you're down two people in the warehouse and I know another one has just turned in their two-week’s notice. What do you mean you're going to shift other resources around? Does this mean I’m fired? What's going on here?”

He just would not answer any of my questions. And then he finally just hung up.

So that felt really bad. And then a week later, on October 7th, I got my final termination notice.

This seemed really blatantly targeted because I had been invited back to work because there was a need for me back at work. I've been there quite awhile. I know how to run all the machines. I know all the processes and I do some processes that nobody else in the warehouse does, including the labeling of every bag that comes out of the place. And the running of some heavy equipment that only one or one other person in the whole place can do.

And so that was it. It just … it doesn't make any sense to do that, to fire a long-time employee that has a lot of expertise in this area. And to fill in my spot with people from the cafes, which that's not their job, but that's what they're doing now—the workers that they've lost in the warehouse, they haven't replaced them with actual warehouse-trained workers. They just replace them with new cafe workers every day.

And I know that the cafe workers go in and do their best. But you have to have a lot of training and experience with these pieces of heavy equipment to know how they work, especially because a lot of them are in disrepair and don't get fixed when they're broken. So you really have to have a lot of subtlety and grace in operating these machines.

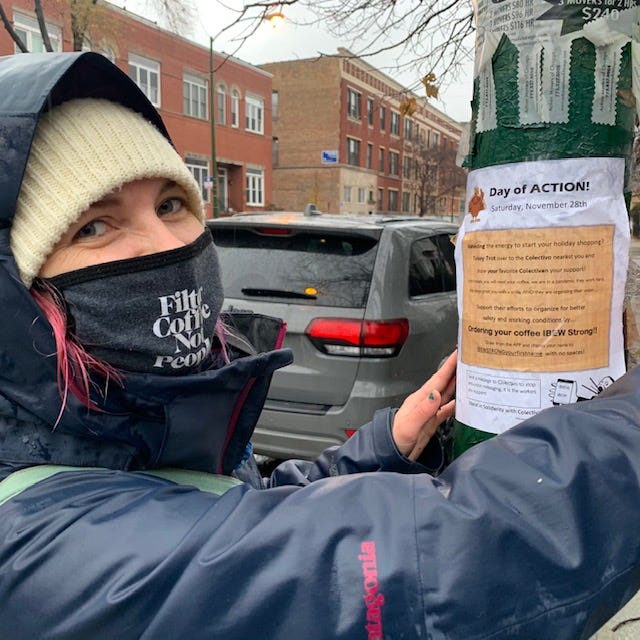

And so it just doesn't make any sense. And the only reason it makes sense is because my name was on the union organizer list. I had been extremely vocal. I had been out putting up posters around the cafes—pro-union posters—and had been very much involved in the union efforts. So I know why they fired me. They won't ever admit that because that would be retaliatory under the National Labor Relations Act. But that's how I ended up getting fired. So I haven't been an official employee since October 7th.

Zoe: And as far as my story, having worked my way up through the company to be one of the barista trainers, which I had done for other companies before, so I'm good at it. I'm not a person who likes to toot my own horn, but I'm good at it. And it kind of all changed when the VOC, or the volunteer organizing committee, list came out with my name on it.

As I said, with our regional managers starting to not make eye contact with me, anytime that I would send out a congratulatory email where somebody would pass their bar certification test so that they could make drinks on the espresso machine completely by themselves—we send those out to the owners and that cafe, the person who just passed their test. We write up all of the great things that they have as far as qualities on bar.

And people respond back with letters of congratulations and well-wishes, and I noticed the CEO either would respond much, much later to my emails than to any other trainer or sometimes not at all. One of the managers at one of the cafes started to request only the other trainer to work with their coworkers at their cafe. So very much targeted on that.

When we got masks that said “IBEW strong,” I started to feel like I had a bit of a target on my back because they knew that I had passed some out. So it really just felt like all of that plus with the captive audience meeting, the energy really changed around me.

They had sent out this letter on October 15th saying that two of the cafes were closing and the Chicago bakery, which was planned to be built this past summer, but then was put on hold from the pandemic was now canceled.

It kind of came with no warning and all of us were in shock. When I went into work the next day on October 16th I found the new head of HR—who I had never met before—in the training lab. And I was kinda taken aback, but I met this person, so started introducing myself and then the head of coffee purchasing essentially came into the room as well and said, “Hey, did you get that email yesterday? And did you have any questions?”

And me still not getting it was expressing my concern for the coworkers who had just lost their jobs, because it was two cafes’ worth of people who had just pretty suddenly not had income or not had a job to go to. So I was mostly worried about them still and then came the, “We'd like you to sit down.”

They informed me that my position had been eliminated. When I asked, “Does that mean I'm done with the company, or can I move into a different role? I would work in one of the cafes for now if that needs to happen.” And they said that there were no positions in Chicago available. If I wanted to move to Milwaukee, I could do that and reapply—not be assured a position whatsoever, but I would have to go through the application process after working there for almost two-and-a-half years.

So they gave me information on unemployment and wished me farewell. I didn't get to finish out my day. I had meetings set up throughout that day and things to talk about with folks and hand out, as far as informational things to send people for the cafes.

And it was incredibly sudden. I was blindsided completely. Then pretty much past that point did not receive much communication from the company whatsoever. My boss, who I was pretty good friends with, I think, never communicated with me. I never got, not even a text. I called my other trainer in tears.

Sorry, I'm kind of getting a little emotional about it too. Because I was just so shocked and I knew that they were going to fight back, but I didn't think they'd fight back like that.

Ashley: I think it's completely expected that you would be emotional or that anyone will be emotional because this is a place that you've put in so much time. Like we were saying earlier, if anything, you folks unionizing is this beautiful expression of, “We believe in this company that we can make better. We can do something better. We can make this better. We didn't just leave. We decided that we wanted to make it better.”

And instead of being embraced or at least being told, “Hey, maybe we don't agree with you, but let's talk about this,” you were gaslit—you were told that unions would be harmful and would harm the company culture and all these very hurtful lies.

And I think that that probably gets missed sometimes—it probably seems like a very black-and-white fight sometimes, but it is really emotional, and it does involve people fighting for their livelihoods.

Zoe: Absolutely.

Ashley: Something that I wanted to come back to is what you said earlier, Zoe, about your manager not making eye contact with you. And I think it's so bizarre how conflict is handled when there's a power dynamic.

So you saying, “Hey, not everything we're doing here is totally cool. Let's talk about it!” Instead of being like, “Oh, yeah, let's do that. Let's talk about it,” people will just avoid eye contact with you. I wonder what that felt like, because to me I'm like, “Oh, this is about something different. This isn't about making this workplace better. It's because I challenged your authority and your ego can't handle it.”

But I wonder, what did that feel like seeing that divide happen?

Zoe: I think that we were all holding our breath once that VOC list went out. We were all curious how folks were going to handle it. This person in particular I think … I was not the most surprised that they avoided eye contact.

I feel like they put everything on the line for the company and I think sometimes in a way where they should take care of themselves a little bit more and maybe … I don't know, they work themselves to the bone. I think that they are fully in it 100% and if the company was going to be against it, then they were going to be against it, too.

So I wasn't the most surprised with how they handled it, but it was kind of one of those like, “Well, I'm here to train somebody. So I got to keep a smile on my face. I got to keep it up and lively. I'm not going to act like anything's different. Let's keep this positivity train going. And I guess pretend that this weird attitude is not really happening.”

Ashley: What do you folks want people to know about your union efforts, and what should people be paying attention to?

Zoe: I remember that there was a meeting where I think Robert summarized it in the best way that I've heard:

We're looking for the three Cs—consistency, communication, and collaboration. It's not going to be that hard, I don't think, once we actually get to bargaining for the contract, because we're not looking for things that are astronomical.

We're literally just looking to be on the same team. We're asking for some accountability for not just the people who work on the floor, but for everybody who works within Colectivo, which right now it's not really a two-way street. It's kind of just on-the-floor workers who get held accountable.

For me, you see a lot of companies with a board of directors, but I would love to see a company with a board of directed, because we know the things that are going on on the floor and the issues that we have, we know first-hand. I hear a lot of very good ideas coming from folks who are down and dirty on the front lines. I want to see those things, those suggestions, those fixes actually put into practice, because oftentimes they're very good ideas because they fix practical issues with practical responses.

Ashley: Thank you both so much for joining me. This has been an incredible conversation and I feel both inspired and angry. So I think we achieved what we were trying to do.

Hold up! You made it to the bottom of this article—thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, you can make a difference by:

Clicking the ‘heart’ at the bottom to say you liked this article

Checking out my Patreon

Sharing this with a friend, on your social media, or anywhere—here’s a button for you to do so:

Share this post