Orange Wine is a Bad Tasting Note

How the words we use to describe coffee often deter the very people we're trying to entice.

⚡ But First! ⚡

Before digging into today’s piece, I wanted to share a quick update about a previous story: I recently wrote about whether or not buying B-Corp coffee (or B-Corp anything) is worth it. This post was my most controversial to date, in that it contains the only negative comment I’ve gotten on the newsletter so far, and that it prompted a friend of mine to send me a very polite counterargument.

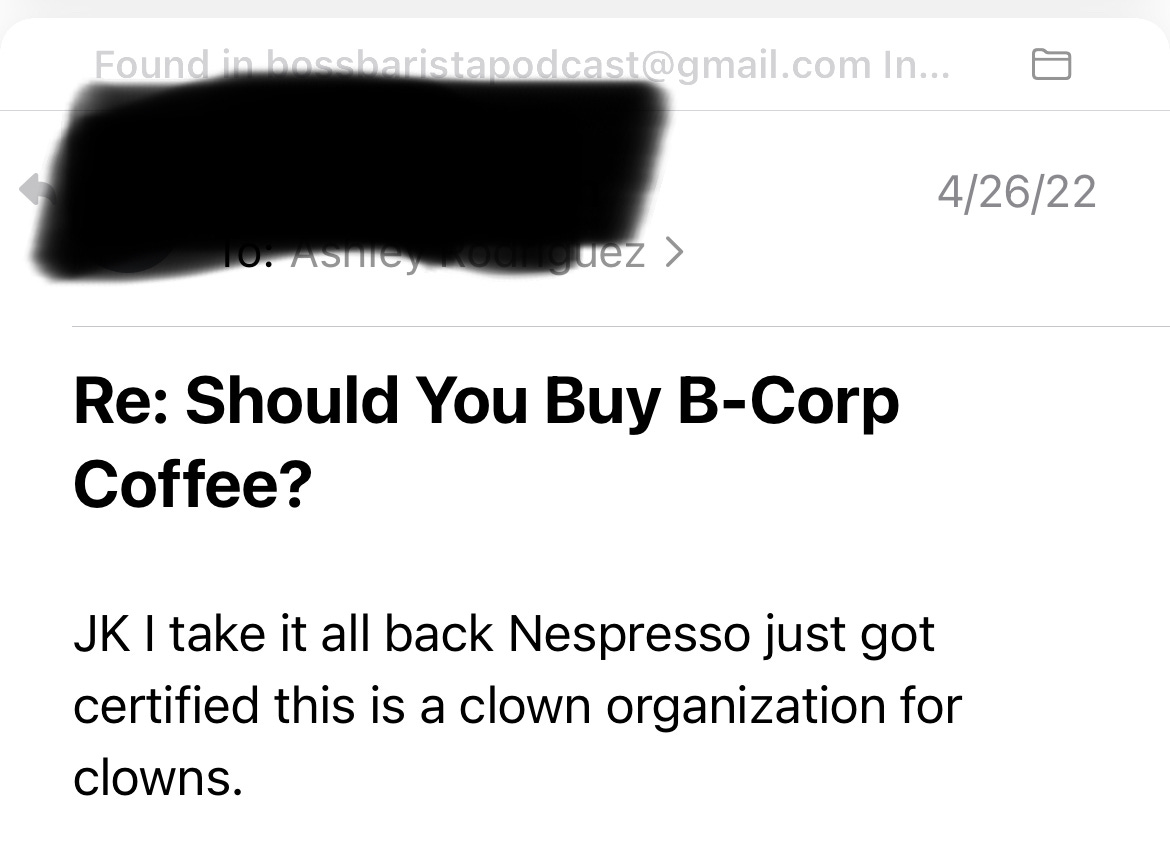

Then, a few days after that, Nestlé announced that the coffee arm of its business, Nespresso, had been certified as a B-Corp business, and that prompted said friend to send me this:

Umm … Nestlé sucks. So much so that a group of watchdog organizations and businesses, including a number of coffee roasters, sent a letter to B-Corp to express their concern. In the letter, they write, “Nespresso’s abysmal track record on human rights from child labor and wage theft to abuse of factory workers is well documented by the media and NGOs. Indeed, Nespresso’s extractive business model is publicly known to be fundamentally at odds with the ethical and just future B Corps…”

It’s a funny feeling to see something you wrote about play out in real time—and it’s kind of exciting that others are taking notice. To be clear, I do think the writers of the letter are primarily concerned that their own B-Corp certifications will be seen as less valuable following Nestlé’s move. But the letter’s content still stands, and it’ll be interesting to see what drives this conversation forward next. Will B-Corp respond? Will Nespresso? I’ll be keeping tabs.

On tasting notes and being set up to fail.

Most foods don’t come with instructions. Tomatoes don’t have notes dangling off their vines that direct, “Best served in a green salad with avocado and arugula.” Ribeye steaks don’t come with a disclaimer: “I’m expensive, so don’t grind me down for hamburger meat.”

Coffee, on the other hand, comes with a ton of disclaimers and directives. On many bags, you’ll find information about a given coffee’s growing region, the name of the farmer who produced it, the varietal, the preferred brew method, the roast level, the elevation, and the tasting notes.

It really makes a difference if more people switch from a free to a paid subscription. I can’t stress it enough: It supports the future of this work.

Unlike a lot of other specialty items—i.e., wine, beer, and chocolate—coffee beans reach most consumers as an unfinished product. It makes sense to give drinkers information so they can best experience the coffee they’re about to brew. But there’s a point where sharing guidance starts looking like dictating the “correct” way to drink coffee.

In my latest podcast episode, I interviewed Gefen Skolnick, founder of Couplet Coffee. Couplet’s coffee bags strip away most of the information that roasters typically add, including tasting notes. That decision was born out of Gefen’s own experiences trying to learn more about coffee:

But it’s like, [consumers] don’t need to know the elevation and sometimes even tasting notes. I mean, when I was picking up these bags and seeing tasting notes, like molasses and stone fruit, and just words that I’d never seen before, honestly, that’s why it took me probably an extra six months to a year to ask the next questions, because it’s just like—if I don’t know this basic terminology of just tasting notes, I’m gonna sound super stupid asking any other question, in my opinion.

Tasting notes can be … odd. As a coffee professional, I can parse most of them—but there’s still only a 20% chance I’ll actually taste what’s listed on the packaging. If a box says “candied orange,” I might get as far as, “Hmm, this tastes kinda sweet and maybe citrusy?” But even that’s not a sure thing.

Conversely, I’ve seen customers—those who don’t taste coffee professionally—agonize over tasting notes. “I don’t want my coffee to taste acidic,” someone might say if they see “lemon” on the label. “I didn’t taste chocolate—was I supposed to taste chocolate?” another might ask after buying a bag. “I don’t know what that is,” someone else might say when they read a description like molasses or stone fruit, or, as I told Gefen, orange wine:

I remember going to this one coffee shop and one of the tasting notes was orange wine. And I remember thinking like, “I know what this is only because this is my job, but that is the only reason why I know what this is and what the fuck? This is a tasting note that nobody else is gonna know!” … because it's another way that we set up folks essentially to fail.

I’m not demonizing tasting notes. At worst, they’re the chaotic neutral of coffee information (versus the name of the farmer [lawful good], the country of origin [lawful neutral], or roast level [chaotic evil]), and I definitely make decisions about the coffee I buy based on tasting notes. But I also wonder if telling consumers what they can expect to taste can create disappointment, or even shame, among those whose experiences may differ. (I’m not the only person who thinks so: my friends at Rabbit Hole Roasters did an IG post on tasting notes.)

This conversation prompted me to think about the other ways that shame inhabits the coffee industry. Usually, if I tell people I make coffee for a living, they preemptively apologize for their brewing setup, or feel like they have to justify why they’re drinking the coffee they’re drinking. And the thing is? I don’t care at all. If you like the coffee you make, that’s amazing.

I think there’s a real missed opportunity in these gaps, in how we can set up consumers for success. What we should be fostering as coffee professionals is a sense of accomplishment—how good it can feel to make something delicious. Imagine being proud of the cup of coffee you’ve crafted for yourself … until you read the tasting notes and think, “Darn, I must have done it wrong. I don’t taste any of that.”

I’m not arguing that all tasting notes should be removed—but I do think that they are often interpreted as diktats from on high, or like a pop quiz that’s all too easy to fail. What if, instead of trying to impress consumers with the funkiest, wildest descriptors we can think of, we begin by considering how we want the drinker to feel, and present information to support that goal?

What’s fun about that approach is that we also open ourselves up to creative expression. Couplet sells a single-origin coffee from Peru, and the “tasting notes” read: “tangy, funky, and bright, Couplet’s Peruvian feels like a beam of light.” This clever rhyming descriptor—a couplet—is inviting and kind, and leaves the actual nitty-gritty of what the coffee tastes like up to the drinker. The brand wants people to feel welcome to the coffee party, and the bag descriptor is designed to achieve that goal.

It makes sense that Gefen picked up on this: Before coffee, she worked in the tech industry as a consumer researcher, and spoke to hundreds of customers to understand their experiences with the companies she worked for. That approach feels striking in a coffee context, because we rarely start by polling people so directly. We don’t do enough to talk with farmers (who are sometimes paid less than what the coffee costs to produce); we don’t start with baristas (who are some of the lowest-paid workers in the supply chain); and we don’t begin by considering consumers, arguably the folks who make coffee viable but can feel too intimidated to really dig in and learn more.

What Couplet does with its bags isn’t going to work for everyone, and perhaps really specific tasting notes will appeal to your targeted audience—maybe you want that person who knows what orange wine tastes like. But I think by looking critically at tasting notes and their purpose on a bag, we can think more broadly about who our audience is and how we want them to feel.

Is it bad that I sometimes think the tasting notes comes off a bit pretentious?! 😅 I'm sure there's an art form to it just like wine tasting...but sometimes I'm like c'monnnnn....

And B-Corp unfortunately now looks like a club of rich kids patting each other on the back for being so wonderful ...and nothing more.